Access to Improved Sanitation

Table of Contents

Summary

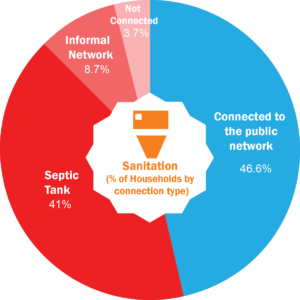

Over 9.2 million households (53.4%) in Egypt are without improved sanitation. Most households use unsealed septic tanks, or informal sewage networks that discharge raw sewage into canals.[1] Deprivation of improved sanitation is disproportionately high in rural regions in Egypt (Upper Egypt and the Delta).

Informal sewage networks carry health risks and pollute ground water , which is a source of drinking water for a considerable number of Egyptians. They also raise the ground water table, which in turn affects the structural soundness of buildings leading to sever damage and even collapse.

How is the lack of access to improved sanitation a problem?

The major concern with the lack of improved sanitation is the general health of inhabitants. Raw sewage can contain pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa and helminthes.[2] These could lead to a range of diseases inducing diarrhea, fever, cramps, vomiting, headache, weakness, or loss of appetite.[3] Lack of improved sanitation in many villages has led to the flooding of streets with raw sewage, [4] directly exposing residents to disease. Raw sewage has also seeped into the ground polluting drinking water exposed to it through leaky pipes or pumped from the ground.

Another concern associated with the lack of improved sanitation is its dangerous impact on the structural safety of houses. In 2012/2013 high ground water accounted for 18% of building collapses in Egypt,[5] a fact exemplified by the Al-Imam Al-Ghazali street disaster in the Imbaba district of Giza. An increase in the level of ground water destabilised a number of buildings, which started to tilt and collapse, while ground floor and basement apartments started to flood with sewage water.[6] This led to the eviction of many families until the sewer problem was resolved. Some buildings were condemned and are to be rebuilt.

Source: CAPMAS 2008. 2006 Census of Population and Living Conditions. Household Access to Sanitation

Who lacks access to safe water in Egypt?

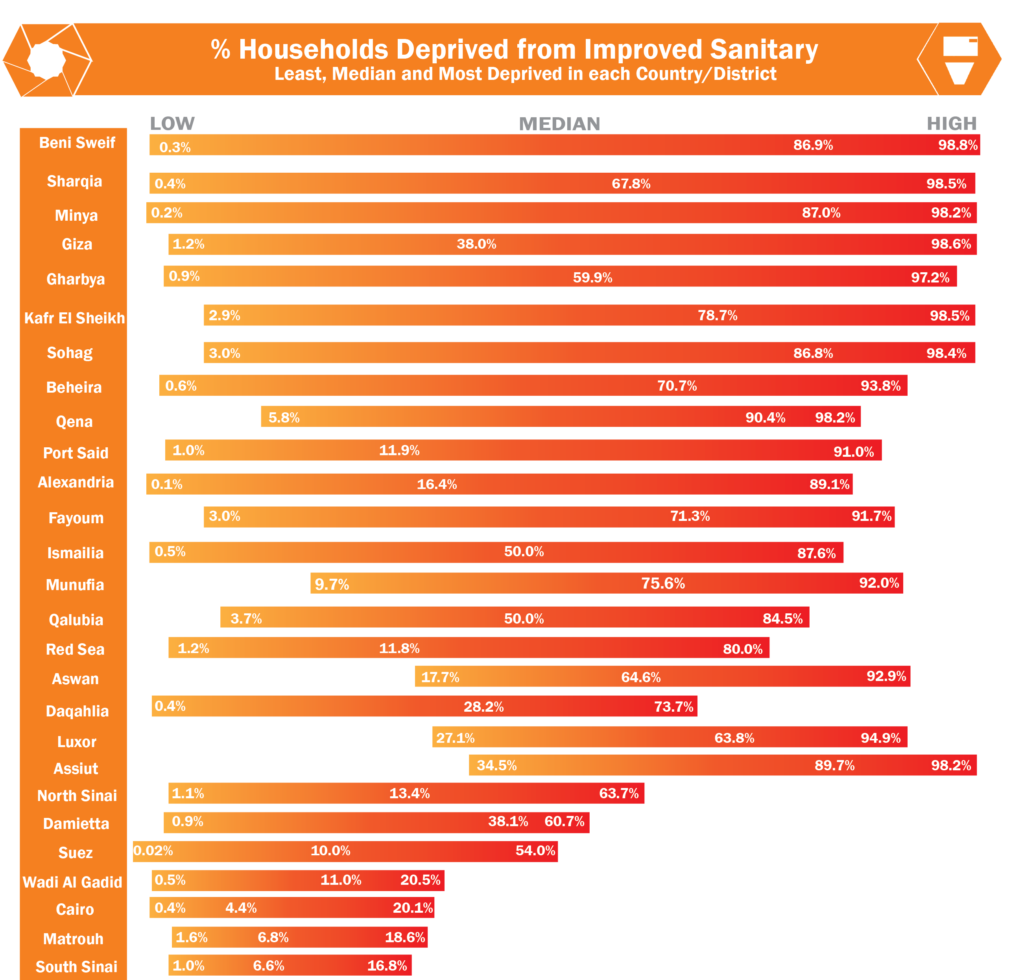

The highest incidence of deprivation from improved sanitation is in rural Egypt, where most villages and a large number of towns lack proper sanitation networks.

While the national average on deprivation from improved sanitation is 53.4%, affecting over 9 million households, four million households live in villages or towns almost completely lacking improved sanitation (Deprivation of 90% or more). Most of these settlements are in Upper Egypt where governorate level deprivation ranged between 64% and 90%. Some 28% to 79% of Delta residents do not have improved sanitation.

Source: CAPMAS 2008. 2006 Census of Population and Living Conditions. Household Access to Sanitation

Why do people lack access to improved sanitation?

The main reason behind the lack of access to improved sanitation is the high cost of infrastructure needed to extend networks in highly dense areas. Recent government sources have stated that this could reach EGP 100 Bn.[7] While much public spending has been diverted to so-called New Cities in a failed attempt to redirect population growth.[8]

Source: CAPMAS 2008. 2006 Census of Population and Living Conditions. Household Access to Sanitation

What can be done?

- Widen current program to build sanitation plants and networks in deprived areas through direct cross-subsidization from state land sales prioritizing the most deprived areas.

- Expand use of low cost technology.[9]

Methodology

Definitions

Sanitation is not yet recognized as a self-standing right, but it is part of the right to adequate housing and the right to an adequate standard of living. Accordingly, the sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights defined the right to sanitation as “the right of everyone to have access to adequate and safe sanitation that is conducive to the protection of public health and the environment”. The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) defines access to improved sanitation as follows: “a household is considered to have improved sanitation if it has sole use of modern or traditional flush toilet that empties into a public sewer, vault (Bayara) or septic system”.

Measurement Tools

The United Nations Human Settlements Program (Un-Habitat) measures the access to improved sanitation indicator by calculating “the proportion of the population with access to improved sanitation, or percentage of the population with access to facilities that hygienically separate human excreta from human, animal and insect contact”. They consider facilities such as sewers or septic tanks, poor-flush latrines and ventilated improved pit latrines as improved sanitation, provided that they are not public.

To ensure the effectiveness of those sanitation facilities, the Un-Habitat defined certain conditions;

- Installation: The facilities should be correctly constructed and properly maintained.

- Sharing: the facilities should be shared by a maximum of two households.

- Sufficient capacity: the septic system should have a sufficient capacity in order not to be clogged. [10]

Methodology for calculating access to improved sanitation indicator in Egypt

According to the international standards and agreements that Egypt is part of and based on the quantitative data published by Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), we consider direct connection to a public sanitation network as access to improved sanitation in most governorates, since most septic tanks are not sealed and/or cleared regularly. Only in Fronteir desert goverorates did we consider septic tanks an adequate means of sanitation as they are not (yet) affected by rising groundwater due to low population densities and the nature of the ground.

Footnotes

[1] CAPMAS 2008. 2006 Census of Population and Living Conditions. Household Access to Sanitation. [2] FAO n.d. Quality control of wastewater for irrigated crop production, Chapter 2 - Health risks associated with wastewater use. http://www.fao.org/docrep/w5367e/w5367e04.htm Accessed 31.08.2016 [3] Australian Government 2010. Department of Health. Disease from sewage. November 2010 http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-enhealth-manual-atsi-cnt-l~ohp-enhealth-manual-atsi-cnt-l-ch2~ohp-enhealth-manual-atsi-cnt-l-ch2.3 Accessed 31.08.2016 [4] “Qura Beni Sweif tahalm bil-sarf al-sihi”, al-Fagr, 16.07.2016 http://www.elfagr.org/2208484 [5] EIPR 2014. Why are Houses Collapsing in Egypt? http://egyptbuildingcollapses.org/ [6] Shadow Ministry of Housing. “Unsanitary Sanitation.” [Documentary] June 2013 مبادرة الحق فى السكن . (2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eiOKYKWRfKc [7] Egypt needs EGP100 Bn to meet water sanitation needs: Minister, Ahramonline, 30.11.2015 http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/172209/Business/Economy/Egypt-needs-LE-bln-to-meet-water-sanitation-needs-.aspx Accessed 31.08.2016 [8] Shawkat, Y and Khali, A. The Built Environment Budget 2015/16 | An Analysis of Spatial Justice in Egypt. 10 Tooba, Cairo. June 2016 http://www.10tooba.org/en/?p=172 [9] Decentralised local systems such as that reviewed in Un-Habitat. Parallel Urban Practice in Egypt. Nairobi, 2015 http://www.10tooba.org/en/?p=144%20Change%20Permalinks%20View%20Post%20Get%20Shortlink%20Add%20Media [10] Un-Habitat. Urban Indicators Guidelines - Monitoring the Habitat Agenda and the Millennium Development Goals. Nairobi, August 2004